Teen Threatened to Be Outed by California High School

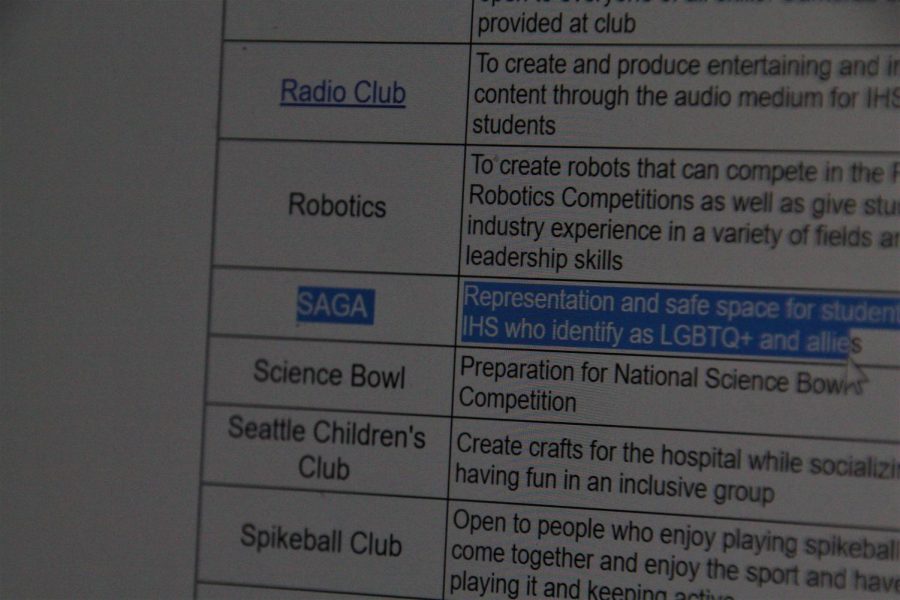

SUPPORT FROM THE STUDENT BODY: “I think the student body does more to spread awareness and support the LGBTQ+ community, like with the creation of SAGA,” Sophomore Jessica Mecum said.

December 10, 2019

On Nov. 7, Buzzfeed News published an article bringing to light the appalling discriminatory action taken by a Catholic High School in California against a lesbian student. In the days following, the story blew up across the nation and Bishop Amat Memorial High School was put under immense scrutiny.

Magali Rodriguez first came out to her friends in middle school, and by her freshman year at Bishop, she was dating a sophomore girl. Rodriguez made sure there were no rules forbidding same-sex relationships. Still, she and her girlfriend kept any kind of public displays of affection to minimum, knowing full well the staff would not be approving.

In the second semester of her freshman year, Rodriguez and her girlfriend were brought into separate conferences with their dean of discipline. According to her dean, their relationship had been brought to the administration’s attention. Rodriguez was told their relationship was wrong, and that their transgressions would be met with a list of rules: she and her girlfriend were prohibited from sitting together at lunch or spending time together during breaks. They would be called to sessions with the dean and the school psychologist often. If the girls failed to follow these rules, the administration threatened to out Rodriguez to her parents.

Issaquah sophomore Jessica Mecum, a member of the student club SAGA (Sexuality and Gender Alliance) said, “You tend to see this more in older generations – it’s natural to them to be a bit prejudiced. I went to a Catholic school, and at confession I shared how I felt and they told me it was wrong.”

For the next two years, Rodriguez and her girlfriend were subject to berating and humiliation, and were constantly under the watchful eye of school staff. Incidents included a staff member telling them they were going to hell and that he was going to get them expelled. Teachers kept constant surveillance on them and made sure they were never within a few feet of each other.

Understandably, this took a toll on Rodriguez. She cried most days before class, her grades dropped, and she experienced intense anxiety when on campus. She and her girlfriend were terrified to show any affection to each other in fear of backlash from teachers. Crystal Aguilar, a close friend of Rodriguez’s said, “I [saw] her attitude towards school change drastically. It went from her being motivated to learn and be at school, to her dreading every day she went. Her sadness because of it overtook her at times.” Rodriguez reflected on that difficult time, saying, “I thought to myself, I don’t know how much longer I can go.”

Up until her senior year, Rodriguez had consented to the rules her school had presented in fear of them following through on their threat. However, she recognized that her mental health was in danger, so she wrote a letter to her parents, addressing everything that had been going on the past three years. “I’m not okay,” she wrote. “And I’m not okay being in this type of environment that’s supposed to be lifting me and encouraging me.”

Her parents were angry – but not because their daughter was dating a girl. They were outraged that the school which they had entrusted to teach and support their daughter had not only taken it upon themselves to force their values onto her, but had continued to harass and demean their daughter and her girlfriend. Rodriguez’s father, Nicolas Rodriguez, expressed his concern saying, “It sounded like a suicide letter . . . It was a huge cry for help.” They immediately took action and removed her from the school. She is now finishing her senior year at a local public school. When Issaquah freshman Phoenix Weatherford was asked his opinion on the story, he said, “I think what [the staff] did is mean, and they should probably get fired.”

Unfortunately, this is not even close to the first time a school, public or private, Catholic or secular, has discriminated against students because of their sexual orientation. A state investigation in Oregon revealed the nature of a high school in the North Bend School District. The principal and an administrator stepped down after the school was found to have continually condoned homophobic bullying by students and teachers of two queer girls, Liz Funk and Hailey Smith. This included other students (including the principal’s son) calling them “faggot” or “dyke”, a student saying “Well, I f***ing hate homos,” then hitting Funk with a skateboard, and a teacher specifically calling out Funk and telling the class that same-sex marriage was essentially the same thing as marrying a dog.

When Funk brought these offenses to the attention of the school’s resource officer, the principal, or the school’ police officer, Funk was met with the same mistreatment she was reporting. She was going to hell and that by being openly homosexual she was asking for harassment, that her sexuality was a choice, and that everyone has a right to their own opinion.

A major difference between this case and Rodriguez’s case is that here, students were responsible for a good portion of the bullying, whereas in California, there was no report of any student harassment – just staff. Mecum believes it is the opposite at Issaquah High School, saying that “most of the teachers try to make this a safe place for the LGBTQ+ community, but students tend to be less accepting and more ignorant. Microagressions happen all the time at our school.”

The Oregon school ended up being ordered by the state to give $1,000 to a local LGBTQ+ organization, pay the students’ legal fees, develop a diversity training program, create a “diversity and inclusion committee,” and apologize to the students.

Back in California, Rodriguez’s story was blowing up. In response to the circulating media reports, President Monsignor Carroll and Principal Richard Beck released a statement claiming the school was dedicated to proving a safe and comfortable learning environment, regardless of sexual orientation. They also quoted the student handbook, which states that BAHS does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, disability, medical condition, sex, or national and/or ethnic origin. Sexual orientation is clearly missing. The statement pinned the blame on Rodriguez and her girlfriend for “displays of affection.” Rodriguez said she never once kissed or held hands with her girlfriend for fear of punishment, even before they were called down by administration. The president and principal claimed it had nothing to do with the fact that it was two girls kissing, but that they were kissing at all. Students said this was false and that straight students often displayed typical high school affection and received no repercussion of any kind.

For most students, this was the first they had heard of the situation. “I never would’ve imagined Amat to be an environment like this,” said an anonymous student. “Once I started to read about the article I was in full shock. I decided to walk out to stand up for her.” Weatherford said, “I’ve never heard of or witnessed any bullying incident at Issaquah, but if I did, I would do my best to stop it.” That Friday, two hundred students walked out at Bishop Amat High to show their support for Rodriguez. Before lunch, the principal made an announcement about the article, and counseling in the library was provided for students with questions. “I feel as if the principal knew they messed up,” said the student. They walked out after lunch, and while teachers were there supervising, they did not act to stop it. The students chanted and held a prayer, while Rodriguez’s friend connected with her on FaceTime.

Mecum speaks on her experience as an LGBTQ+ student at Issaquah High, saying, “I think minorities are treated better at our school than most places, but there’s still room for improvement. Most people at our school are accepting of me, although some people have treated me differently after finding out my sexuality and what I identify as. I just want people to not treat others differently when they find out who they are. It hurts.”

In the end, the students showed administration that their actions were unacceptable. But think of all the students across the country – across the world – that are not lucky enough to have their stories unearthed. No child deserves to be treated like a criminal, especially not at school. Remember: if you see something, say something. It is everyone’s responsibility to watch out for each other.