The Debate Behind the Potential Return of the Woolly Mammoth

October 20, 2021

These days, “Jurassic Park”, the popular film series, is looking less like a fictional blockbuster and more like a prediction of the future. The most recent indicator of this is the unveiling of the new genetics company Colossal and their intention to “see the Woolly Mammoth thunder upon the tundra once again.”

The company, led by Harvard professor of genetics George Church, received an investment of $15 million on Sept. 12 from CEO Ben Lamm. This will allow them to put their ambitious plan into action, though they claim to have begun taking steps as early as 2018.

As one might expect, the science behind the project does not lend itself to simple description. Contrary to popular belief, there will be no cloning involved – this can only be done with a living creature. Instead, Colossal will use the gene-editing mechanism, CRISPR, to essentially swap out parts of the Asian elephant DNA sequence for parts of the Woolly Mammoth sequence with the intent to give the elephant important traits from the mammoth, especially those of which are cold-resistant. In other words, they will genetically modify the Asian elephant, the closest living relative to the Woolly Mammoth, so that it looks and acts more like a Woolly Mammoth. This includes features like shaggy coats, smaller ears, cold-adapted forms of hemoglobin, and excess adipose tissue production.

Therefore, they are not literally “bringing back” the Woolly Mammoth, but rather creating a genetically-engineered hybrid between the Asian elephant and the Woolly Mammoth, which they have named the “mammophant.”

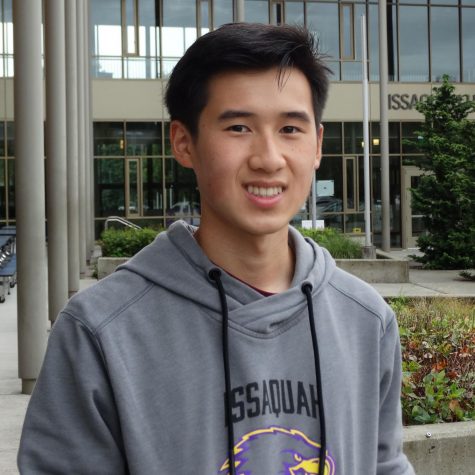

Junior Jonathan Wang says, “The science seems plausible.” He remarked that it would certainly be an interesting experiment, but added, “I don’t know what they’re planning to do with the mammoths…It wouldn’t be adjusted to the current environment and climate. I mean, the reason the Woolly Mammoths went extinct is because they couldn’t adapt to the warming climate, so I doubt it would be able to survive.” This is a valid concern that many experts outside of Colossal have brought up, but Colossal seems less interested in how the climate will affect the mammoths, and more in how the mammoths will affect the climate.

In fact, according to Colossal, concern for the climate is the driving motivator for their project. It is the belief of some scientists that prior to their extinction, grazing animals of the Ice Ace, including mammoths, served to maintain the northern grasslands they inhabited, as well as the permafrost below the dirt, by knocking down trees, trampling bushes and grass, and compacting snow. Their absence, Church and others assert, allowed for the permafrost to warm, and thus, for the release of greenhouse gases. Colossal reasons that putting this new generation of mammoths in the arctic could help fill the gap created 10,000 years ago.

To freshman Audrey Short, this sounds like too much theory and not enough substance. She says, “I think Colossal should conduct some sort of test to prove their prediction before they just jump right into it.” This opinion is shared by many genetic experts, including Love Dalén, a professor in evolutionary genetics at the Stockholm-based Centre for Palaeogenetics. Dalén told NPR during an interview in September that he does not foresee Colossal’s project making any serious impact on the warming climate, regardless of whether or not it succeeds. “There is virtually no evidence in support of the hypothesis that trampling of a very large number of mammoths would have any impact on climate change,” he said. Sophomore Eli Galit says, “There’s no way that they can ensure that those behaviors will be recreated and effective. I think there are more effective ways to combat climate change, like regulating large corporations’ outputs of greenhouse gases.”

Should you prescribe to Dalén’s view that mammophants are probably not going to help solve climate change, by no means does this render the described technology useless. In fact, this is the foundation of the argument of many of Colossal’s critics: the power of CRISPR is immensely valuable, and therefore should not be wasted on long-gone creatures, especially when the validity of the motivation for doing so is as heavily debated as in the case of Colossal. Instead, these critics say geneticists should focus their energy and money on helping currently endangered animals – which includes the Asian elephant – and pull them out of the pit of endangerment.

Senior Cate Menting says, “We should be proactive and save animals before they’re gone rather than trying to reverse the extinction after it happens.” However, Wang pointed out, “Bringing back animals that are already extinct would be useful for scientific information on how they evolved.”

The aforementioned issues are just a few of the concerns raised in response to Colossal’s plan. Nonetheless, Church and his company seem confident in their ability to create the mammophant, as well as the benefit these creatures will serve. They expect to create a mammophant embryo within the next six years, though their method for doing so is not entirely certain at the moment.

Plan A, according to Colossal, is to develop an artificial uterus in which the embryo will gestate, but the science behind this task is very new and bumpy, and there is no guarantee it will lead to success. Joseph Frederickson, a vertebrate paleontologist and director of the Weis Earth Science Museum, told NPR he absolutely did not think the creation of a mammophant embryo would be happening “anytime soon.” Dalén was also quoted saying that he believes Colossal’s goal of six years is “exceptionally short” and “seems pretty ambitious.”

Plan B has also sparked controversy in the science community. Church has said that if creating an artificial uterus were to fail, Colossal has not ruled out the possibility of using live Asian elephants as surrogates to carry and birth the genetically engineered hybrids. “I feel like we need to be confident that [using Asian elephants as surrogates] won’t hurt the elephants,” says Menting. Galit agreed, explaining that it seemed to him like there was a “high risk” for something to go wrong. He pointed out that protecting the Asian elephant is especially crucial considering it is listed as an endangered species according to the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFW). Evolutionary biologist and mammoth specialist at the Natural History Museum in London told CNN in a recent interview, “Let’s say it works, and there’s no horrible consequences. No surrogate elephant moms die. The idea that by bringing mammoths back and by placing them into the Arctic, you engineer the Arctic to become a better place for carbon storage. That aspect I have [a] number of issues with.”

In any case, should Colossal succeed in creating a mammophant, there is already a park in Siberia awaiting the new species’ arrival. The park was officially founded by geophysicist Sergey Zimov in 1996 and is run by the Northeast Science Station (NESS), of which Zimov is president of. “Pleistocene Park” is meant to replicate the mammoth steppe, the Earth’s most extensive biome at the time of the late last Ice Age, and home to the now extinct Woolly Mammoth. The goal of NESS is similar to that of Colossal; to “restore high productive grazing ecosystems in the arctic” and “mitigate climate change.” They contend that the restoration of grazing animals in in the Arctic would have a cooling effect on the climate. Already, they have introduced a variety of species of herbivores to the 8-square-mile-park, including the reindeer, moose, bison, musk ox, and yak.

However, it seems NESS is hesitant to admit to their wilder aspiration of bring back the Woolly Mammoth. For one, there is no mention of it on the park’s official website. More telling is The Conversation journalist and post-doctoral researcher Charlotte Wrigley’s visit to the park and her documented conversations and experiences with the scientists there.

Wrigley reported that at the time, NESS was using a massive tank to replicate the behavior of a mammoth – knocking down trees and trampling bushes – so as to produce the desired effect on their mammoth steppe environment. She claimed that, according to the NESS, this was only a temporary stand-in, and they were hoping to soon have the real thing. But, Nikita Zimov, Sergey Zimov’s son who helps him run the park, also told her, “You have a lot of people believing God, and they don’t like this mammoth return. So, I try and use it to bring attention to the park, but I don’t want any of the criticism.” Nevertheless, just a few weeks after Wrigley returned home, the Zimovs met with Church, appearing to confirm the connection between their two projects.

It should be noted that Colossal is not the only company or foundation working to revive the Woolly Mammoth. Most notably is Revive & Restore, a California-based company founded in 2012 that promotes “the incorporation of biotechnologies into standard conservation practice.” The company is more upfront about their support of the de-extinction of the Woolly Mammoth – not only does Revive & Restore specifically cite Dr. Zimov’s research and Pleistocene Park, but it also claims responsibility for introducing Church to Zimov, and asserts that it was Zimov who vied to bring mammoths to Pleistocene Park.

All this to say that while the spotlight is on Church and Colossal at the moment, there are a number of organizations working toward the revival of the Woolly Mammoth, whether or not they wish to openly speak on it. For now, the world will just have wait and see how the Woolly Mammoth resurrection project plays out. While experts like Dalén, Herridge, and Frederickson are clearly skeptical, as scientists they are also naturally curious, and thus, open to the possibilities. “I am absolutely fascinated by this,” said Herridge. “I’m drawn to people who are technologically adventurous, and it is possible it will make a positive difference.”