Robot Rockstars and Man-made Musicians: An Exploration into Fictional Pop Idols

May 26, 2020

From the beginning of time, humans have been worshipping something. Whether it be gods and goddesses or plants and animals, devotion was always poured into some kind of deity. As we continued to pray and serve, idols were built, not in attempts to replace the gods, but to represent godliness the closest way that a human can achieve. Is it any surprise that our contemporary use of this term is found within the title of “pop idol?” Deities and gods are still worshipped today, but many people have turned to celebrities and musicians as the newest target of devotion. Stan culture puts bands like “BTS” on nearly celestial pedestals, pilgrimages on Twitter ensue from “barbz,” Nicki Minaj fans, as they seek to prove why the rapper reigns supreme. “STREAM SAY SO REMIX FEAT. NICKI MINAJ!” could be seen everywhere around the internet as Doja Cat fans insisted other social media users to stream the song on repeat to boost the remix into the number one spot on the Billboard Chart. Celebrities are given such fervent adoration that they have replaced the ideas of what godliness can look like. However, with technology reaching new heights, is there a way that we could produce the ideal idol in less time than it takes to train one? Are humans now capable of not only creating the perfectpersonality, but an entirely new persona too? Introducing the fictional musician. They can be found from all over musical history, a concept that has been alive for so long, but now, with the help from major improvements in tech, are able to reach new levels of life. Whether they are used for marketing or for the pure love of a story, where do we draw the line with this frankensteinian trend and how do we know when the merging of fiction and reality has gone too far?\

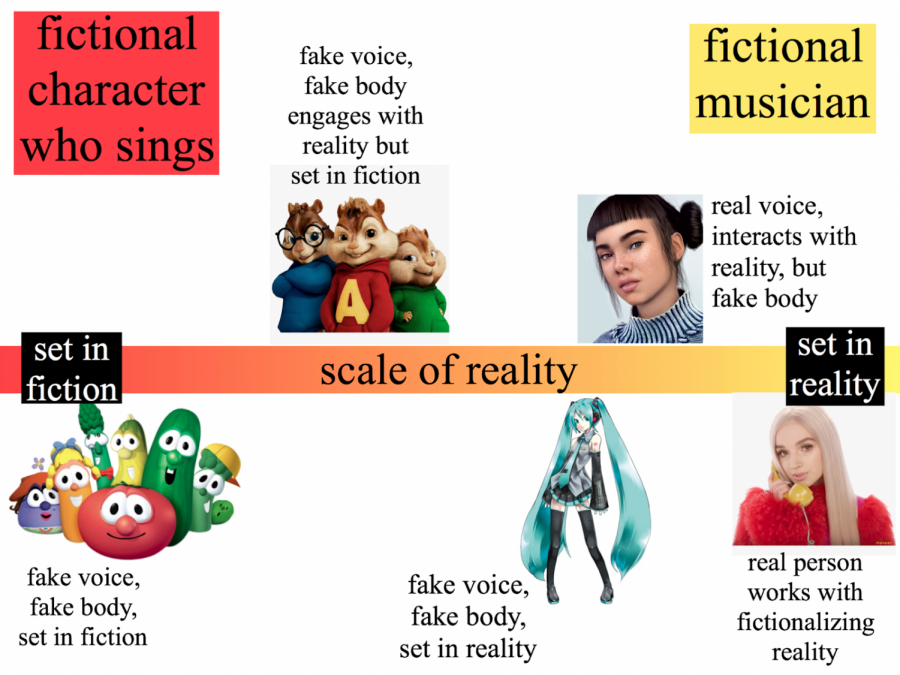

Before delving into the history of fictional musicians, let us establish the differences between a fictional character that sings versus a fictional persona that is a musician. An example of the former is “Veggie Tales.” The Christian children’s show about talking vegetables is known for simplifying Bible stories into easy to understand and entertaining renditions for kids. What is less popularly known about the children’s series is that they have released multiple albums with the classic cast of characters singing covers of songs from popular 80s hits, “Bob and Larry Sing the 80s,” to kid-friendly versions of country songs, “Bob and Larry Go Country.” These are fictional characters singing and producing albums, but do they count as the fictional musicians previously discussed? No. The major difference is that the Veggie Tales cast was not produced with the sole intention of being the primary face and persona of a musical group; instead their music is more of a byproduct from their primary mission of being an animated children’s show. This same logic would apply to excluding the likes of Mickey Mouse–“Mickey Unrapped”–along with other Disney character albums and other animated show characters which have produced music after their initial identities were created with intentions other than being the fictional personas for producing music.

One of the earlier examples of the fictional musician phenomenon is “Alvin and the Chipmunks” or the commonly used shorthand, “The Chipmunks.” According to Anjelica Oswald in an article for Business Insider, “Ross Bagdasarian Sr. …spent $190 of his last $200 on a tape recorder in 1958 to speed up his voice. The result was ‘Witch Doctor,’ a song with a high-pitched chorus that became an astonishing hit. From this came the inspiration for ‘The Chipmunk Song (Christmas Don’t Be Late),’ which was released later that year, and thus, the chipmunk trio was born.” Bagdasarian Sr. created The Chipmunks with the intention of creating a new novelty record hit. The aforementioned chipmunks–Alvin Seville, Simon Seville, and Theodore Seville–were the faces and mouths of Bagdasarin Sr.’s sped up voice and comedic tunes, and even though the trio become animated in 1961 with “The Alvin Show,” their intent when created still counts them as one of the earliest fictional musicians. A more contemporary example is the alternative rock band, Gorillaz. Created in 1998 by Damon Albarn and artist Jamie Hewlett, the fictional band comprises four members: lead singer 2-D, bassist Murdoc Niccals, drummer Russel Hobbs, and guitarist Noodle. Over the years as the group has produced music, voice actors and singers for the band have circulated–except for 2-D who remains voiced by Albarn. Junior Ray Widjaja says, “[fictional personas allow] more freedom. Thinking from a perspective of someone that isn’t oneself I would think would give one more ideas.” Widjaja’s statement is exemplified by the discography of Gorillaz as the band has been able to explore and experiment with a wide range of genres over the years including alternative rock, art-pop, hip-hop, electronic, and trip-hop. Despite the band’s deep fictional lore, they are framed to be existing in this reality, with Noodle becoming a global ambassador for the British automotive company Jaguar Land Rover, and their music videos, which often merges real life people interacting with the animated band members. Without delving too deeply into their individual lores and backgrounds, some other examples of fictional musicians include virtual pop-singer “T-Babe” (2000), CGI Japanese Idol “Aimi Eguchi” (2011), internet persona for the artist Joji, “Pink Guy” (2014), and the virtual K-Pop group for the game” League of Legends”, “K/DA” (2018). This list does not contain every single example of a musician who has chosen to undertake a fictional persona. However, that is because this design decision has proved itself to provide many benefits, adding to its popularity. Senior Kameren Bennett comments on these pros saying, “I think [having a fictional persona for your music] is a strength because you can hide who you are and the things that you do are done through a character. It’s a secrecy that builds a lot of curiosity about who you are.” Although many artists behind the characters choose to make themselves known, many choose to embrace the level of privacy and the freedom it allows.

On Aug. 31, 2007, the world and the music industry would never be the same again. That fateful date in the late summer marked the official release date of one of the first true robot rockstars: Hatsune Miku. Created by Crypton Future Media, Miku is the face of the synthetic singing program “VOCALOID” and is described by Emilia Petrarca in an article for W Magazine as, “a 16-year-old pop star from Sapporo, Japan. [With] neon blue hair, which she wears in pigtails, and bright blue eyes.” What is it about Miku that counts her as a fictional musician? Her voice is one factor; the way in which the software works is that it allows users to synthesize songs by plugging in lyrics and melodies. Using pre-recorded vocal samples of the artist Saki Fujita, the program creates singing and enables the user to change the tone, vibrato, and specific pronunciations with the voice. Miku is the face for most of the music that artists create using this program, for example two popular songs of “hers” being “World is Mine” and “Rolling Girl” are both viewed by the public as songs credited to Miku rather than the respective creators, artists Nico nico! and the late Wowka. Having hit critical acclaim through her concerts where she performs onstage as a moving and dancing hologram, to her collaborations with artists such as Lady Gaga and Pharell Williams and with the pizza chain, Dominos, Miku’s work has proven to make her an international superstar. Overall, Miku’s vocal technology, and her work in holographic concerts, marks one of the many milestones in the technology which brings life into digital personas like herself. Achievements like this not only add dimension to the fictional, but resurrect the real as described by Trigtent in an article posted onto Medium, “Who needs iTunes, Spotify, old videos and live concerts when you too can personally own a dead celebrity for your entertainment?” The ethics of this technology has yet to be fully delved into and explored, but for now, we are able to recognize and witness the rapid changes which are occurring in this field.

One of the newest fictional pop idols that has hit mainstream audiences is Lil Miquela. She is described by Kaitlyn Tiffany for Vox as “[Being] beautiful. She has a ton of followers. She is mysterious, yet her personality is fantastic… She was made by a computer to look as much like a hot and charming human being as possible without scaring people. Her body casts a shadow. She has flyaways and freckles.” Depicted with a more off-beat but still very trendy style, she is “19 years old” and a Brazillian-American who is constantly seen donning her signature space buns. Lil Miquela is a synthetic influencer and singer who has taken social media by storm. Having recently released her new single, “Machine,” on April 23, Lil Miquela has branded herself to not only be a musician but an activist of the influencer level. Having avidly supported the “Black Lives Matters” movement and faced off with fellow CGI being Bremuda–in lore, another robot like Miquela made for the company “BRUD”–a previous hacker of Miquela’s account who titled herself as a “Trump supporter” and touted alt-right views. Despite the love that Lil Miquela gets from fans everywhere, her existence cannot exist without some concerns and criticism. One of these major critiques is that everything Lil Miquela is is completely fabricated, leading to an exploitation in subjects such as activism and race. Lil Miquela is the creation of Trevor McFedries & Sara Decou, and neither are the voice behind the persona,which continues to remain a secret. However, from the beginning, they have crafted the image, beliefs, and actions of this character. When it comes to her appearance, Lil Miquela is ethnically ambiguous. As a CGI creation, she can technically look like anything, which allows for her to be able to get the “best of everything,” picking traits from women of color that have been typically idealized and hunted after, while still maintaining the ideals of typical European beauty standards. This on a surface level does not feel completely worrying. After all, Lil Miquela is a digital entity, of course her traits can be specifically tailored to the ideal, she is a robot. However, there has got to be something that is morally wrong about using the aesthetic appearance of a light-skinned colored woman as the fictional persona for a voice actor who we do not currently know the identity of. With the previously mentioned Miku, the fictional persona maintained a character that depicted the same race, at least with the voice actress who lent vocal samples for the program. Unlike “Alvin and the Chipmunks,” even though Lil Miquela is technically described as a robot, that does not remove her from the perception and pre-composed ideas of race that the audience holds. Meanwhile, race has no equivalent perception for the chipmunks because they are simply chipmunks, and they do not benefit from the visual perceptions of race and ethnicity. By portraying herself as a woman of color but with the “beauty” of ethnic ambiguity, is this digital idol who is essentially the unbeatable ideal influencer taking space that could be held by an actual woman of color? Another moral calamity that arises when discussing Lil Miquela is her “left-leaning” branding. In 2018, according to Jonathan Shieber for Tech Crunch, “Brud, the actual company behind one of Instagram’s most popular virtual influencers… has raised millions of dollars from Silicon Valley investors.” What draws many to Lil Miquela is her “cool-girl” appeal and the similarity in political beliefs that she may hold with her audience. However, once again, Lil Miquela is a character. Specifically, a character whose creators greatly benefit financially from her perceived beliefs–which are primarily on subjects that would not impact her at all since she is a completely digital creation. This scenario leaves a similar negative taste in my mouth like when branded accounts try to seem “trendy” on Twitter, except instead it is a sharper level of distaste, as this instance feels rather exploitive of a movement which many people, specifically black people, have died or faced harsh consequences for. Whatever the case may be, fans of Lil Miquela will remain, and another fictional musician will continue to produce music for the masses.

Ultimately, as we have discussed and dissected the history and morality of the fictional musician, a question still stands. Does having a face for one’s music even matter? Widjaja says that a musican’s image is, “Not at all important” when it comes to the music he listens to, continuing that he, “[Cares more about] the music over the person.” Whatever may be the case, the ultimate realization that can be taken out of all of this is that the fictional musician is here to stay, and it is up to us to define what we want from the experiences created by them.