Being products of their environment, often stuck in a bubble, it is hard for people to think outside of their own community and daily routine. As a high schooler in the US, it is easy to complain about waking up early for school, crowded parking lots, bad lunch food, and not having a seat on the ever-filling bus.

Besides the select few who travel and spend a year-or years-in other parts of the country or other countries, most are used to their school system and its specific pros, cons, and quirks. In America, students often have an array of classes ranging from Geometry to US History to Chemistry to English Literature in all four years of high school, preparing them for college, gap year, or a career of some kind. Most students are around eighteen when they graduate, somewhat burnt out and ready to see a new sea of faces for a change. But in England, students are only required to go to school until they are sixteen, followed by a career or University. From Oxford Royale, “A UK university education focuses on depth, not breadth. While students can choose to study two subjects (called ‘joint honours’), most will choose to study only one.” Meanwhile, Oxford Royale continues, “in the USA, however, while it is possible to start out by choosing just one subject (or major), it’s as usual to enter university on a much more general course, such as a liberal arts degree.” According to the same source, UK universities give a bit more independence, while “in the USA, professors act quite a lot like secondary school teachers. It is their job to ensure your grades are as good as they possibly can be, and they will try to make your studies as effective as possible.”

Junior Maddie Powell, who went to elementary and middle school in Hong Kong, discusses the class options: “Going into year 10 (freshman year) we would select our favorite classes we took in middle school and commit to taking them for the next two years. We would spend those two years learning material that we would then be tested on during the spring semester of our sophomore year. People would not go to school except to take their tests after spring break. Then they would repeat new class selection and take two years of class to be tested at the end of their senior year. This way of teaching allowed kids to really personalize their high school experience. Classes like dance, drama, PE, and economics were offered as two or four-year-long classes that were advanced and exam-based. In America, classes in the art and PE department are often taken for an easy A and to meet a graduation requirement. There, people were passionate about those electives and it created an environment where people worked hard, regardless of how academic the class was considered.”

Sophomore Rares Rus, who went to school in Romania up until summer 2023, said in Romania there was no choice over what classes you do, and states about going to school here, “It still shocks me I can choose my own periods. [In Romania] you had them in different orders. As an example, Monday you have math, history, chemistry, PE, other classes, next is different, every day in the week is different. I like this probably more.”

Testing can differ from country to country, like China and Finland. In China, according to Oxford Royale, “Schools lean very strongly towards the memorisation and retention of facts. This is demonstrated in the gaokao, the university admissions exam, which depends on what a student can memorise and repeat; analysis and critical thinking are not tested.” Finland is known to be a strong example of a country with a school system that is not a fan of standardized testing. From World Economic Forum, “Filling in little bubbles on a scantron and answering pre-canned questions is somehow supposed to be a way to determine mastery or at least competence of a subject. What often happens is that students will learn to cram just to pass a test and teachers will be teaching with the sole purpose of students passing a test. Learning has been thrown out of the equation.”

Freshman Sally Davis, who went to elementary school in Spain, had a quite a different experience, saying, “Something I’d change in the US is maybe the work load they give us in elementary and middle school. In Spain, we took really difficult tests from the very beginning of elementary school, and everyone began to learn English in preschool. We’d all take French in fourth grade,” adding, in her opinion, that “in general, school in Spain prepared you for future and more difficult years in school, while here, they really don’t.”

Powell had a similar experience when it came to grading and tests and the strictness of teachers. Powell says, “In America, I feel like electives are easy A’s and my work ethic towards those classes is reflective of that belief. Teachers at international schools have a very high expectation set for their students. I have felt like studying for hours and completing all assignments at my high school is above and beyond the expectation. This can be seen in the fact that my school makes the lowest grade a student can receive on any assignment a 40% meaning they expect students to hand in so little work that a passing grade needs to become more achievable. In Hong Kong, the opposite was the norm. I felt like my teacher’s expectations and my classmate’s dedication challenged and encouraged me. Although electives and required courses in America do not share that environment, many advanced classes I have been in have come close. The difference is seen in the electives. I remember being in swim class and being told I was unathletic because I could not swim more than 25 laps in 12 minutes. Instead of being graded on attendance, my PE grade was based on the performance they thought was athletic for a girl my age. I was not a fan of this grading system!”

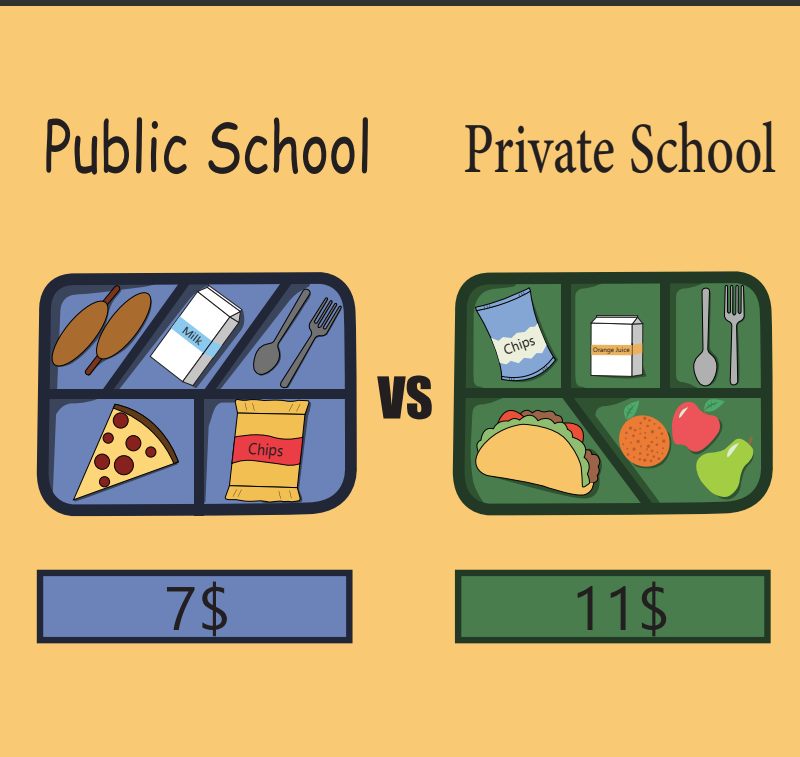

Both Kayla Tehero, senior, and Davis mention something in common when it comes to going to school abroad. Tehero went to first and second grade in Versailles, and could even see the Palace of Versailles from her apartment. Tehero says, “Meals were amazing, they had a chef, it was like a three-course meal. I never brought lunch to school because it was like a really nice lunch.” Similarly, Davis states, “The food all schools in Spain gave us were super healthy, three course meals,” though adds this interesting bit: “If we didn’t eat it, we’d be forced to by a counselor or we’d have to sit in the principal’s office until we did.”

Again in common were Tehero and Davis when it came to recess. Tehero remembers “there [was] not really a playground area, kids would play soccer on the concrete,” with Davis remarking, “And we didn’t really have a playground – it was just a wide open area, fenced in, where we could run around and play soccer, if we brought our own ball.”

Think your school day is long? Another article from Oxford Royale discuses school hours, saying, “South Korean students in secondary school can be at their desks for 14 to 16 hours. The standard school day is 8:00 until 4:00, which in its own right is long by international standards. But students in the last couple of years of school will then go home for some dinner, and head out again to a private school from 6:00 to 9:00 for intensive revision. There may well be another couple of hours of homework to do even after all of that.” Davis, in Spain, had a similar experience, saying, “School days were much longer – from 9:00 to 5:00 – though we had a two-hour lunch break in the middle of the day.”

When it comes to the age you enter school, there are not many discrepancies, except when it comes to the specificness of the Netherlands or Finland. In explaining how birthdays can be either an easy or difficult insinuator as to when your child should start school, Oxford Royale states, “The solution to this in the Netherlands is that all students start school on their fourth birthday, whenever that may be, so throughout the year there are always new students joining. While this does mean that older students get more time to settle in and make friends, it does at least mean that students should be at a similar development level by the time their first day at school rolls around.” Finland is known to have students start school at an older age than other countries. From infoFinland.fi, “Comprehensive education normally starts during the year when the child turns seven. All children residing in Finland permanently must attend comprehensive education. Comprehensive school comprises nine grades,” though it was extended in 2021, and now “after comprehensive school, all young people have to study until they graduate from secondary education or reach the age of 18.” Interestingly, infoFinland.fi also states, “If the child or young person has only recently moved to Finland, he or she may receive preparatory education for comprehensive education. Preparatory education usually takes one year. After it, the student may continue to study Finnish or Swedish as a second language if he or she needs support in learning the language.”

While in American schools students are used to saying goodbye to their teacher, or teachers, at the end of the school year, in Finland, according to infoFinland.fi, “Children often have the same teacher for the first six years. The teacher gets to know the students well and is able to develop the tuition to suit their needs. One important goal is that the students learn how to think for themselves and assume responsibility over their own learning.”

Powell gives intel on how the classes and schedule system were both similar and different to middle and high school in America. Powell says, “Firstly, we spent our middle school years taking every course our school had to offer. We had trimesters and would switch from graphic design, food technology, fashion design, computer science, etc. We would switch between biology, chemistry, and science every trimester with an entirely new class and teacher. Social studies would switch between history, geography, philosophy, and religious studies (not a religious school). We were also required to take PE year long as well as two foreign languages.”

There can be more to learn besides math, history, science, and reading and writing. School is an important place to learn social expectations, task management, planning, schedules, working with others, and critical thinking. Japan goes a different route when it comes to the things taught besides the core subjects. From Oxford Royale, “Moral education has been taught informally in Japan for decades, but it is gaining ever more prominence in the Japanese curriculum, being taught in some schools on a par with subjects such as Japanese or mathematics.”

In the end, it is up to a mix of opinion and fact to decide which country has the best school system. You can look at charts and look for what you want; best test scores, highest graduation rate, best attendance, etc. Powell said it best with, “I think that learning can happen anywhere and school is what you make of it.”