Lana Del Rey and the Post-Magnum Opus Curse

March 23, 2021

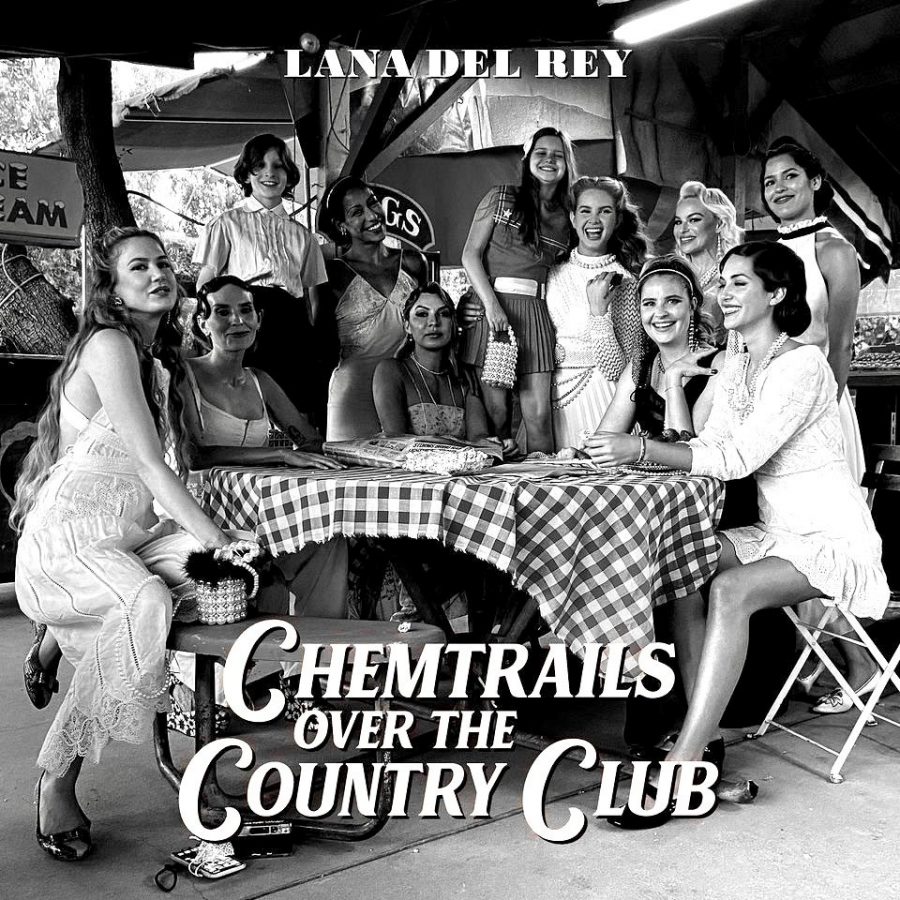

Once you reach the peak, where do you go? Once you reach the west, once your destiny is manifest, when sunset skies and fields are no longer amber but a darker, polluted brown. That idea of the once-great is present throughout Lana Del Rey’s art, applied in varying shades of criticism and irony towards Americana. Now, the New York-born singer/songwriter faces the same question herself. Following the release of her magnum opus, 2019’s “Norman [expletive] Rockwell”, which saw her examine the inflated egos of male artists, the conflict in loving them, and the similarities between such relationships and the American experience, comes her new LP, “Chemtrails Over the Country Club.” It is a beautiful, messy sketchbook, filled with unfinished portraits of life in the heartland and musings on the impacts of fame for a woman whose very ascension to popularity has reflected back a dirty mirror on that ever-coveted American dream.

Lana Del Rey’s career has been one saturated in American stereotypes and iconography: diners and diamonds, killers and Kennedy mansions, Coca-Cola and Coney Island. As a result, she has become somewhat of a symbol herself. To her fans, it is an endearingly sarcastic aesthetic, to her critics, a tone-deaf take on patriotism. On “Chemtrails,” she leans in to her own archetype in more ways than one. “Wild at Heart,” in what would otherwise be a standout track, uses the exact same instrumental background in the chorus as her exquisite 2019 song “How to Disappear.” It comes off as lazy and recycled, an unusual choice for an artist who is generally so intent on remaking her image completely with each album. Long-time listeners of Del Rey are used to her lyrical self-portraits by now— she is wild, simultaneously a victim and a rebel, and, above it all, an American girl who wants to believe. Her self-referencing lyrics are so brazen in this album, however, that it feels tired, less like Lana is making tongue-in-cheek depictions of herself and more like she has run out of things to say.

As a listener, it can be unfair to compare one body of work to another. But in the white-hot glow of the masterpiece that was Lana’s previous album, it is nearly impossible to not listen to “Chemtrails” in that context, especially because it feels like an unorganized collection of outtakes and half-done songs from her last work. Many of the songs were recorded during the same period as “Norman [expletive] Rockwell,” with some, like “Yosemite,” even being intended for her 2017 album “Lust for Life.” The project lacks cohesiveness both lyrically and sonically as a result, ranging from the auto-tuned alt-pop of “Tulsa Jesus Freak” to the country twang of “Breaking Up Slowly.” It is not that an artist as talented as Lana could not make these different styles blend together (she is more than capable), but that she does not really make an effort to. The listener is taken track-to-track in a way that feels rushed and chaotic, and the album never really settles in to itself. One cannot help but think it would be better as a collection of bonus tracks to her last LP or a transitional EP released before her next full project; these songs just do not merit a separate, independent full-length album.

“Chemtrails” has fragments of genius. The closest Del Rey gets to a thematic motif is when she addresses the complexities of fame. “White Dress” introduces the topic as she idealizes her waitressing job before fame through breathy vocals and an obvious-yet-poignant metaphor for innocence, while the superior “Dark But Just a Game” reveals her cynical take on the concept. The song, written after she attended Madonna’s Oscars after-party, was given its title by the album’s producer, Jack Antonoff. The two concluded that while fame can certainly make “the best ones lose their minds,” it is best not to take it too seriously. It is not a new take and much easier said than done, but anyone familiar with Del Rey’s casual social media presence and flippant attitude towards public statements understands she is being completely sincere. Plus, it sounds beautifully crisp, sung over a hazy electric jazz guitar. The other musical standout moment arrives at the bridge of “Dance Till We Die:” the tempo suddenly changes to an upbeat blues-rock sound, something that could easily be heard on a Fiona Apple album or a funky ‘70s classic.

As “Chemtrails Over the Country Club” comes to an end, I find myself thinking more about Lana than the project itself. It is indicative of the album’s unremarkable nature, but adversely a great insight into where Lana Del Rey is in her artistic trajectory. Off the high of her previous album, she is rightfully confident and more daring in her choices, a reason that the album is her most sonically experimental to date. Conversely, her musical choices are messier and less self-aware. As someone who has spent so much of her career both praising and criticizing the idea of America and its contrasting realities, she has become remarkably like it: wrapped up in symbolism, in love with the past, unsure of her future, and still, despite it all, creating beautiful art and beautiful ideas through the misty blue haze.

David • Sep 11, 2021 at 3:32 am

You’re so harsh on what I think is truly a masterpiece of an album. It’s a step down from NFR for sure, but I think after going so big, she had to go small for Chemtrails. White Dress, Chemtrails, Tulsa Jesus Freak, Wild at Heart, Dark But Just a Game and Yosemite are top tier Lana!

Also I loved the same of How to Disappear in Wild at Heart – its not a sample from the chorus at all, its a sample from the instrumental bridge, which extends and improves it.